Pulsara Around the World - February 2026

January Recap The start of 2026 was on the slow side for our events schedule, with our team heading to the Florida Fire & EMS Conference, the...

5 min read

Team Pulsara

:

Jul 11, 2024

Team Pulsara

:

Jul 11, 2024

The mental health of America’s youth is under duress, and it didn’t start with COVID-19. It’s a problem that’s been a much longer time coming.

In 2023, authors led by Mayo Clinic psychiatrist Tanner Bommersbach, M.D., MPH, examined trends in young people’s use of emergency departments. What they discovered was startling: From 2011 to 2020, the weighted number of pediatric ED visits related to mental health rose from 4.8 million to 7.5 million – an average increase of 8% a year. “Significant linearly increasing trends were seen among children, adolescents and young adults,” the investigators found, “with the greatest increase among adolescents and across sex and race and ethnicity.”

By 2020, mental health-related visits accounted for more than 13% of all pediatric ED visits – and then came COVID. Now, several years later, kids are still paying a heavy price.

“It’s not just a local problem. There’s a big boom of pediatric mental health crises nationwide,” said EMS physician Brandon Morshedi, M.D., DPT, FACEP, FAEMS, NREMT-P, FP/CCP-C, assistant medical director for Metropolitan EMS (MEMS) in Little Rock, Arkansas and a faculty physician in the Department of Emergency Medicine at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences. “Here in our service area, it was our second most common call type in every month of 2023, right behind ‘sick person.’ The causes are multifactorial, including a lack of adequate and efficient community outpatient mental health facilities and resources, and the emergency department seems to be where a lot of these kids end up.”

In the Little Rock area, where MEMS transports around 77,000 patients a year, that soaring pediatric mental health call volume started contributing to crunches in the emergency department: All the service’s mental and behavioral health patients under 18 had to be taken to a single facility, Arkansas Children’s Hospital (ACH), to be checked out and medically cleared before being transferred to a behavioral health center. “MEMS was transporting about two behavioral patients a day, and they were seeing a lot of additional behavior patients arriving by private vehicle and other EMS providers,” recalled MEMS Clinical Manager Mack Hutchison. Medics ended up delayed, and distressed kids endured long waits.

The situation wasn’t working well for anyone – but MEMS already had a solution in hand.

Since 2020, Metro EMS had been using the Pulsara platform for communication. An app-based system that unifies care teams across departments and organizations, it links MEMS crews to partners at hospitals and elsewhere to simplify and streamline their joint care of patients. The platform brings all communications onto one dedicated patient channel, replacing radio reports, phone calls and other methods. This allows EMS to document their assessments and initial interventions, then share a detailed prearrival notification with ED counterparts and other care providers. This expedites care processes, reduces duplication of communication, improves accuracy and ensures everyone has the same common operating picture.

With funding from the state, MEMS initially adopted Pulsara for care of time-sensitive emergencies like stroke, STEMI and trauma, where it enabled sending key information ahead and sharing it with specialists like neurologists and cardiologists. The platform has some demonstrated benefits in these areas.

“The genesis of that was through the governor’s STEMI [ST-elevation myocardial infarction] Advisory Council,” said Hutchison, a member of that group. “Among the first things we looked at was whether all the EMS agencies in Arkansas could obtain 12-lead EKGs, and if so, could they transmit them ahead to the hospital?”

Most could get the 12-lead, the committee discovered, but many couldn’t transmit them to the hospital. The Pulsara platform was their solution, and the state also helped hospitals obtain it. It worked so well that hospitals’ use quickly expanded from time-sensitive issues to nearly all categories of patient presentation.

So why not kids in crisis? Well, conventional EMS wisdom has discouraged such an approach.

“As medics, we always thought pediatric behavioral patients had to be medically screened before they could go to a behavioral hospital,” Hutchison said. “But in the ER, they’re waiting for up to 24 hours and taking up bed space and resources other, sicker children could be using.”

It made sense to take such children directly to their needed specialists, circumventing the busy children’s hospital entirely – if it could be done safely. So, MEMS assembled a committee that examined the issue and worked on a protocol to allow it.

The committee came up with a protocol that let EMS crews conduct rapid medical screenings and, if young behavioral health patients meet the required criteria, take them directly to behavioral health facilities.

The criteria are straightforward: Patients can bypass the ED unless they have an injury requiring medical attention, a questionable ingestion, a chronic medical diagnosis or are acutely ill. If the initial responding medics determine a patient is eligible for direct transport, they use Pulsara for a quick call to line up a suitable destination (MEMS has five to select from for these patients) and add providers there to the patient’s care channel. They fill remaining patient info into the app en route, so receiving staff are informed and prepared when they arrive.

In the program’s first 11 months, MEMS encountered 4,424 psych patients, of whom 758 were pediatric. Of those, 379 were taken to emergency departments, and 58 weren’t transported – but 321 were taken directly to behavioral facilities under the new protocol, avoiding the ED. None needed subsequent 911 help or bounced back. That amounted to a 46% reduction in the number of pediatric psych patients requiring clearance at ACH (a rate that has continued to improve even since Pulsara featured MEMS’ use in a recent case study).

“Being able to take pediatric patients straight to truly definitive management, and not having to go sit on the wall in a hospital that can’t accept these patients for an extended period of time, makes everybody happier,” said Morshedi. “The medics are happier, Arkansas Children’s Hospital is happier, the behavioral health facilities are happier because they’re getting patients straight from the field, and the parents usually come with them for the intake process. We get our crews back in service quicker. It prevents secondary transfers. So, it’s been a win all around.”

And there’s room for additional victory: Of the 379 young patients who went to the ED, 276 actually qualified for the new protocol but couldn’t go straight to behavioral facilities due to reasons like bed availability, facility response timeliness and family preference.

The program has been so successful that MEMS is now piloting a similar approach for adults.

Pulsara isn’t mandatory for EMS personnel in Arkansas, but its benefits and ease of use have prompted lots of providers to embrace the app. And while it does represent a new step in the prehospital care of patients, it replaces multiple others.

“The medics see for themselves that it works and improves times and patient outcomes, but you have to kind of balance the number of things you’re asking them to do out there on an encounter,” said Hutchison. “We still use our ePCR software too, but we try to find some give and take. What can we take away that you don’t have to do if you use Pulsara? One of those things is the radio report to the hospital. So there were little things that helped people come on board. That also included partnering with hospitals and doing studies. After Pulsara was implemented, for example, we had one stroke facility that decreased door-to-needle times by about 58%. So sharing that success with the medics helps persuade more medics to use it.”

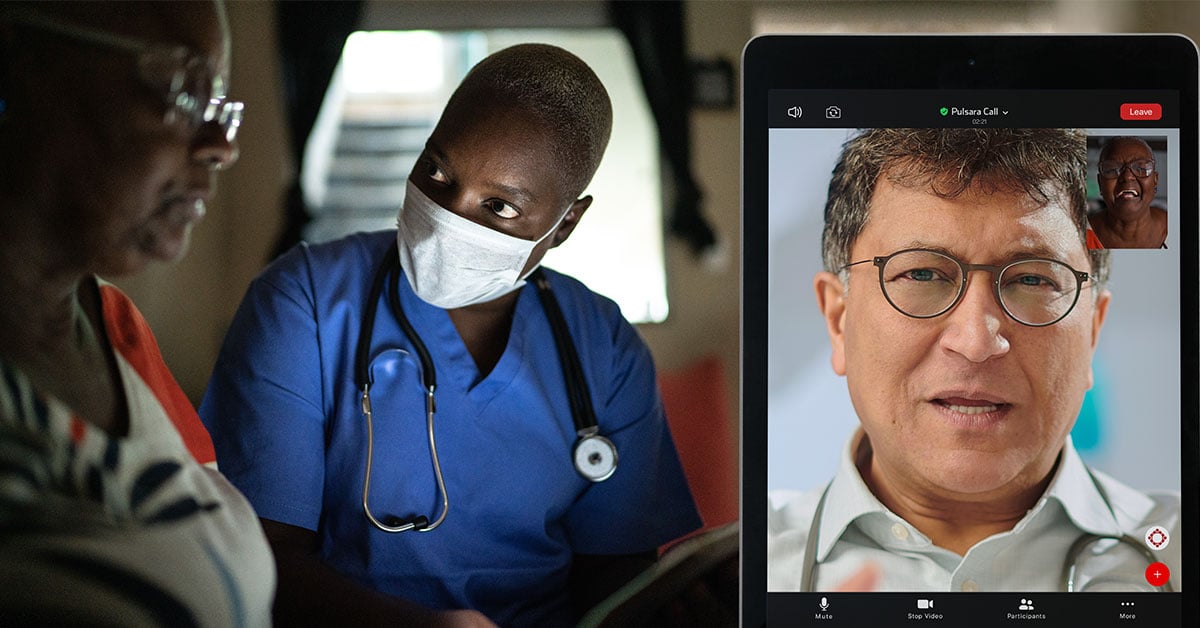

The platform has also been useful to Air Evac Lifeteam, the air-medical giant that operates in 18 states. In Arkansas it lets Morshedi, the service’s medical director, video conference easily with his flight crews.

“It’s basically like FaceTime but all within the Pulsara app,” he said. “The crews just add me or any of the physicians here as a consult into the channel they already have between them and the receiving facility, or even if they don’t have a facility assigned yet. We can engage in audio and video calls, lay eyes on the patient and talk directly to them. We see this being useful with our refusals and nontransports.”

Arkansas also recently passed a bill that codifies principles of the federal government’s late ET3 (Emergency Triage, Treat and Transport) plan into state law. This allows EMS to navigate lower-priority patients to alternative destinations or treat and release them and still get reimbursed by Medicaid – but it requires a physician consult.

“We knew then we’d be using Pulsara a lot more,” added Morshedi. “We have a nontransport rate of 15%–20%, right around the national average. Imagine if you could recuperate the revenue lost from not transporting those patients! So this could be a platform for agencies to generate some revenue by doing what they’re doing anyway. They’re not going to increase their nontransport rate just so they can go make more money, but it’s a way to stop losing money.”

Download the case study to learn more about how MEMS is transporting pediatric behavioral health patients directly to behavioral health facilities—resulting in a 44% decrease of pediatric behavioral health patients transported to the ED.

January Recap The start of 2026 was on the slow side for our events schedule, with our team heading to the Florida Fire & EMS Conference, the...

Recent research shows how Pulsara was successfully leveraged to connect more than 6,000 COVID-19 patients to monoclonal antibody infusion centers via...

At Pulsara, it's our privilege to help serve the people who serve people, and we're always excited to see what they're up to. From large-scale...