Pulsara Around the World - February 2026

January Recap The start of 2026 was on the slow side for our events schedule, with our team heading to the Florida Fire & EMS Conference, the...

2 min read

Team Pulsara

:

Dec 13, 2018

Team Pulsara

:

Dec 13, 2018

EDITOR'S NOTE: Special thanks to Arron Paduaevans for writing today's blog post. You can connect with him on LinkedIn.

As emergency medical professionals — including paramedics, emergency medical technicians, and firefighters — one of the greatest risks we encounter is damage to our own mental health. As emergency medical technicians and paramedics, we are the first line of emergency responders to accidents, crime scenes, and natural disasters. As such, we encompass a serious and vital role in emergency preparedness.

As first responders, it is our duty to provide emergency services in the immediate aftershock of crises and disasters, both manmade and natural. Time spent in affected areas can be a few moments up to several months, often working long days under demanding and traumatic conditions, observing the human injuries, physical devastation and psychological destruction that can go along with tragedies and catastrophes.

As such, first responders may receive physical harms or psychological damages from the services they must provide. Recently, researchers in emergency readiness have concentrated on “environmental contacts and other risk factors, such as structural instabilities within the built environment, which may impact first responders’ physical health” (Wheeler, McKelvey, & Thorpe, 2002). Injuries to first responders’ mental health are just as big a concern. Since mental health issues may not be seen as they are often hard to perceptibly recognize and identify, their manifestation may significantly affect first responders’ capacity to provide effective health services (Benedek, Fullerton, & Ursano, 2007).

According to Perrin, DiGrande, & Wheeler (2007), researchers have established that, following involvement in emergency situations, first responders “experience elevated rates of depression, stress disorders, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) for months and sometimes years.” First responders who do not have appropriate disaster response training have a significantly larger risk of getting a PTSD diagnosis following the emergency response situation (Perrin, DiGrande, & Wheeler, 2007). Even with appropriate disaster preparedness training, first responders might not be ready for the mental challenges once in the disaster situation, as even the best, most extensive training cannot fully mirror a true disaster setting. Additionally, according to Rutkow, Gable, and Links (2011), “most trainings do not explicitly include sufficient content regarding psychological self-aid” (p. 56).

Given this data, actions must be taken to guard first responders’ psychological welfare through the creation of federal, state, and local laws and policies that ensure standardized psychological safeguards for first responders. Specifically, three areas in which ethical issues should be a focus are:

1. Mental health screening for first responders

2. Licensure portability of mental health care providers

3. Workers’ compensation for mental health claims (Rutkow, Gable, & Links, 2011)

Rutkow et. al (2011) share that though many areas have sanctioned legal safeguards for first responders’ mental health, “more could be done in light of ethical concerns about stigma, justice, equity, and allocation of scarce resources” for length of a declared emergency. Permanent legal resolutions are essential to guarantee that first responders have simple and easy access to psychological health care before, during, and after disaster and emergency situations.

Agencies that consider and respond to these issues may better protect and defend first

responders’ psychological health, thereby reinforcing their own emergency readiness systems.

References

Benedek, D., Fullerton, C. & Ursano, R. (2007). First responders: Mental health consequences of

natural and human-made disasters for public health and public safety workers. Annual

Review of Public Health 28. 55-68.

Perrin, M., DiGrande, L., & Wheeler, K. (2007). Differences in PTSD prevalence and associated

risk factors among World Trade Center disaster rescue and recovery workers. American

Journal of Psychiatry 164.1385-1394.

Rutkow, L., Gable, L. & Links, J. (2011). Protecting the mental health of first responders: Legal

and ethical considerations. Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics 2. 56-61.

Wheeler, K., McKelvey, W., & Thorpe, L. (2007). Asthma diagnosed after 11 September 2001

among rescue and recovery workers: Findings from the World Trade Center Health

Registry. Environmental Health Perspectives 115. 1584-1590.

January Recap The start of 2026 was on the slow side for our events schedule, with our team heading to the Florida Fire & EMS Conference, the...

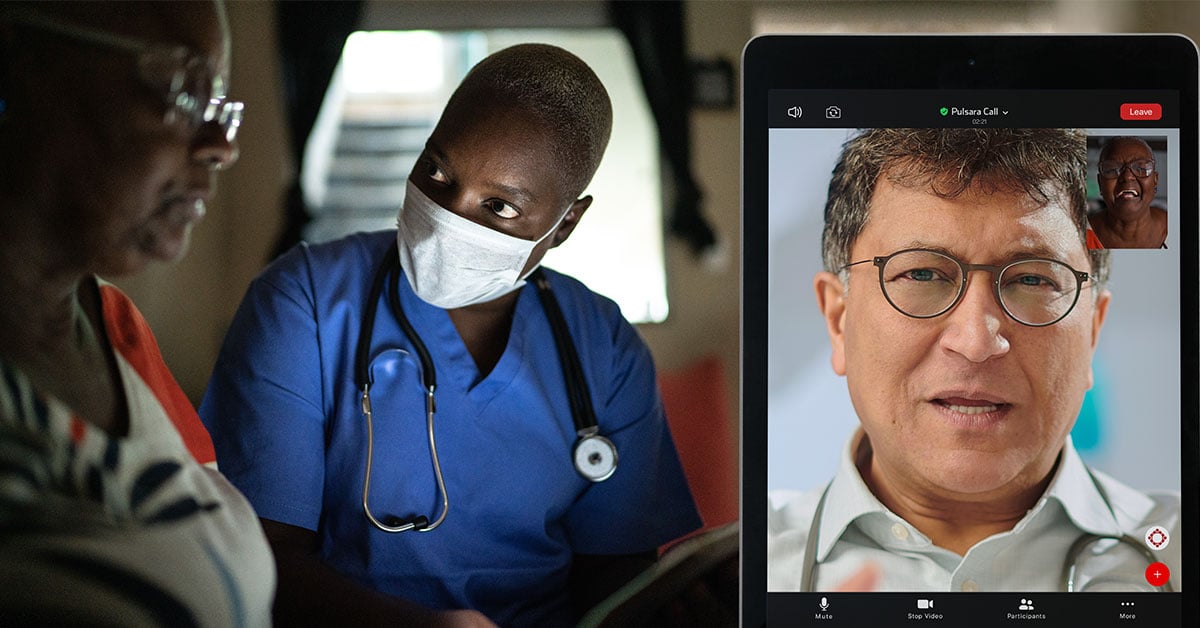

Recent research shows how Pulsara was successfully leveraged to connect more than 6,000 COVID-19 patients to monoclonal antibody infusion centers via...

At Pulsara, it's our privilege to help serve the people who serve people, and we're always excited to see what they're up to. From large-scale...