Pulsara Around the World - March 2026

February Recap From neuroscience symposiums to EMS expos, our teams traveled to five shows in February. Our events schedule is slowing down in March....

The key is to remember that kids get sick differently than adults and that physical findings may be more subtle

EDITOR'S NOTE: This article originally appeared on EMS1.com. Special thanks to our guest author, Jonathan Lee, for EMS1 BrandFocus.

__

I have been fortunate during my career to be able to specialize in pediatrics, which has given me a unique perspective. It is pretty common to hear paramedics say that kids are difficult, but the truth is, kids are just different. When it comes to trauma, the basics are all the same: ABCs, bleeding control, and rapid transport. There are a few things that I do differently with children than when managing adults, and I am certain these can make things better for both you and your patient.

Paramedics find kids stressful, not just in trauma. Lack of exposure, lack of training, and inappropriate/unfamiliar equipment are known problems that need to be addressed before you are in front of a patient (Cottrell et al, 2014).

One of the most effective ways I manage this stress is by reducing cognitive load. When I am with the patient, it’s important to identify clear priorities first. In trauma, it’s easy: ABC, bleeding control, and transport. Anything outside of that can be deferred until those priorities have been addressed. Using whatever memory aids are available can also help reduce the stress that comes with trying to calculate drug doses or choosing the right-sized equipment.

Nobody will dispute the important role caregivers play as historians and in the consent process. I have learned there are two big benefits of engaging caregivers early:

The evidence tells us intubating kids in the field doesn’t make things better, and in fact, might make things worse (Harris et al 2022). Maintaining a patent airway, along with adequate oxygenation and ventilation, is my main priority.

If I can accomplish this with an oral airway and a bag valve mask, then I am comfortable that my treatment is timely and appropriate. If this fails, then I will escalate to supraglottic airways or intubation as required. Intubating children is not without risk, and the decision to pass the tube must provide enough benefit to offset the risks.

It’s often said that kids get sick really fast, but they just get sick really differently. With adults, I rely heavily on blood pressure, but hypotension can be one of the last signs of cardiovascular collapse, especially as patients get younger. This means if I wait for hypotension to begin resuscitating kids, it can be dangerous.

Elevated heart rate, skin changes (including pallor, mottling, and delayed capillary refill), along with altered level of consciousness, are signs of poor perfusion in kids and are my cue to begin resuscitation. Look for perfusion, not hypotension.

The science for resuscitation in pediatric trauma is lacking, and most of what we do is adapted from adult medicine. Important questions like “When is the best time to start fluid?” or “What fluid should be used?” and “Should we be giving TXA?” don’t have answers yet.

The current approach to trauma in kids is damage control resuscitation. This focus is on stopping bleeding and minimizing hypothermia, coagulopathy, and acidosis (the trauma triad). What does that mean? First, keep the patient warm. Remember that blood is probably better than saline, so limit high volumes of crystalloids. Finally, hypotension is a late finding in children, so permissive hypotension does not have the same support as it does in adults (Gilley & Beno, 2018).

The one difference between adult and pediatric physiology that I find most important is the head. In younger kids, the large head has a big impact on airway management. A shoulder roll is one of my go-to interventions to keep the airway open.

The size of the head contributes to head injuries being one of the leading causes of death in pediatric trauma, but it can also change the way the injuries present. Infants with unfused skulls may present with delayed symptoms of increased intracranial pressure because they have extra room to accommodate swelling. In the very young, they can lose enough blood into their head to cause hypovolemia (ATLS, 2018).

Try a rolled-up towel under the shoulders to help manage the pediatric airway. (Jonathan Lee)

Along with head size, bone density can cause injuries to present differently in children than in adults. It means that kids typically don’t lose as much blood from long bone fractures as adults do. Pelvic fractures are much less common in kids, but the mortality is higher than in adults (Herman et al, 2017). This is likely a reflection of the large amount of energy transfer required to break the less brittle bone. The different bone density also means kids are less likely to get rib fractures and flail chest, but are more likely to have underlying damage like tension pneumothorax and pulmonary contusion (ATLS, 2018).

The key is to remember that kids get sick differently than adults and that physical findings may be more subtle.

The potential for non-accidental injury (NAI) should always be considered during scene size-up and history gathering – not just to fulfill your legal obligations, but because you are typically the only healthcare provider on scene. You may be the only one privy to the information that may identify signs of abuse.

For me, one of the most important and difficult parts of NAI is remaining impartial. Regardless of what appears to have happened, my job is to care for the child and family, not to determine guilt.

These situations can be chaotic, and information will evolve and change. I cannot imagine the consequences of being a parent dealing with accusations and an injured child at the same time, so the prospect of NAI should not change patient care.

Pain in children, especially prehospital pain, is historically poorly managed (Rutkowska & Skotnicka-Klonowicz, 2015). While pain is incredibly complicated, there are a few musts for every patient. First, assess and quantify the pain. Start with non-pharmacology forms of pain management, such as ice, splinting, and distraction, which are relatively easy and effective. Non-narcotic forms of pain medications are not better or worse than narcotics. They act differently and should be considered.

The idea of “masking symptoms” is dated, and the decision to withhold narcotic analgesia should only be made based on clinical concerns, such as airway and cardiovascular status (Krause et al, 2016). Finally, anxiety is an important component of the pain experience and should not be ignored.

The fact that trauma patients do better at trauma centers should not be new to anyone (Demetriades, 2006). Likewise, children taken to a pediatric trauma center do better than those treated at adult trauma centers, but fewer of these exist (Sathya 2015).

The hard part is determining which kids need a trauma center. CDC field trauma triage guidelines have been criticized for under-triaging pediatric patients, as they identify those who may die or require ICU care but risk missing those that are less severe but still require interventions (Wyrick 2014).

Current pediatric-specific triage guidelines all have identified weaknesses and still require refinement (Van der Sluiis, 2018). What we do know is that physiological criteria (like GCS <12) are far more sensitive than the mechanism of injury. Kids do best at children’s hospitals, so work within local protocols to make sure the patient gets to the appropriate facility.

References

American College of Surgeons. Committee on Trauma. (2018). ATLS®: advanced trauma life support student course manual.

Demetriades, D., Martin, M., Salim, A., Rhee, P., Brown, C., Doucet, J., & Chan, L. (2006). Relationship between American College of Surgeons trauma center designation and mortality in patients with severe trauma (injury severity score> 15). Journal of the American College of Surgeons, 202(2), 212-215.

Cottrell, E. K., O'Brien, K., Curry, M., Meckler, G. D., Engle, P. P., Jui, J., ... & Guise, J. M. (2014). Understanding safety in prehospital emergency medical services for children. Prehospital Emergency Care, 18(3), 350-358.

Gilley, M., & Beno, S. (2018). Damage control resuscitation in pediatric trauma. Current Opinion in Pediatrics, 30(3), 338-343.

Harris, M., Lyng, J. W., Mandt, M., Moore, B., Gross, T., Gausche-Hill, M., & Donofrio-Odmann, J. J. (2022). Prehospital Pediatric Respiratory Distress and Airway Management Interventions: An NAEMSP Position Statement and Resource Document. Prehospital Emergency Care, 26(sup1), 118-128.

Hermans, E., Cornelisse, S. T., Biert, J., Tan, E. C. T. H., & Edwards, M. J. R. (2017). Pediatric pelvic fractures: how do they differ from adults?. Journal of children's orthopaedics, 11(1), 49-56.

Krauss, B. S., Calligaris, L., Green, S. M., & Barbi, E. (2016). Current concepts in management of pain in children in the emergency department. The Lancet, 387(10013), 83-92.

Myers, S. R., Branas, C. C., French, B., Nance, M. L., & Carr, B. G. (2019). A National Analysis of Pediatric Trauma Care Utilization and Outcomes in the United States. Pediatric emergency care, 35(1), 1–7. https://journals.lww.com/pec-online/Abstract/2019/01000/A_National_Analysis_of_Pediatric_Trauma_Care.1.aspx

Rutkowska, A., & Skotnicka-Klonowicz, G. (2015). Prehospital pain management in children with traumatic injuries. Pediatric Emergency Care, 31(5), 317-320.

Sasser, S. M., Hunt, R. C., Faul, M., Sugerman, D., Pearson, W. S., Dulski, T., ... & Galli, R. L. (2012). Guidelines for field triage of injured patients: recommendations of the National Expert Panel on Field Triage, 2011. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report: Recommendations and Reports, 61(1), 1-20.

Sathya C, Alali AS, Wales PW, et al. Mortality Among Injured Children Treated at Different Trauma Center Types. JAMA Surg. 2015;150(9):874–881. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2015.1121

Wyrick, D. L., Duke, J., Joubert, K., Recicar, J., & Maxson, T. R. (2014). The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) field triage criteria do not accurately predict the need for trauma team activation in the pediatric population. Journal of the American College of Surgeons, 219(4), e186.

van der Sluijs, R., van Rein, E. A., Wijnand, J. G., Leenen, L. P., & van Heijl, M. (2018). Accuracy of pediatric trauma field triage: a systematic review. JAMA surgery, 153(7), 671-676.

About the Author

Jonathan Lee is a critical care paramedic with Ornge in Toronto, Canada, with over 25 years of experience in 911, critical care, aeromedical, and pediatric critical care transport. Jonathan’s teaching experience includes classroom, clinical, and field education as well as curriculum development and design across a number of health professions.

Jonathan Lee is a critical care paramedic with Ornge in Toronto, Canada, with over 25 years of experience in 911, critical care, aeromedical, and pediatric critical care transport. Jonathan’s teaching experience includes classroom, clinical, and field education as well as curriculum development and design across a number of health professions.

He is currently delivering KinderMedic, a program he developed to improve the confidence and competence of prehospital providers caring for acutely ill children. In addition to his clinical practice, he is also adjunct faculty in the Paramedic Program at Georgian College. Jonathan is a freelance author and has been invited to speak across North America and Europe on topics such as pediatrics, analgesia and stress.

Jonathan has previously served on committees for professional organizations, including the Ontario Paramedic Association and NAEMT. He is currently pursuing a Master of Science in Critical Care from Cardiff University. Jonathan can be contacted via Twitter and LinkedIn.

![]()

Managing pain for pediatric patients can be intimidating, but not to worry—there are some principles you can keep in mind to help. Check out 10 Things You Need to Know About Pediatric Analgesia to learn about managing pain in pediatric patients.

February Recap From neuroscience symposiums to EMS expos, our teams traveled to five shows in February. Our events schedule is slowing down in March....

January Recap The start of 2026 was on the slow side for our events schedule, with our team heading to the Florida Fire & EMS Conference, the...

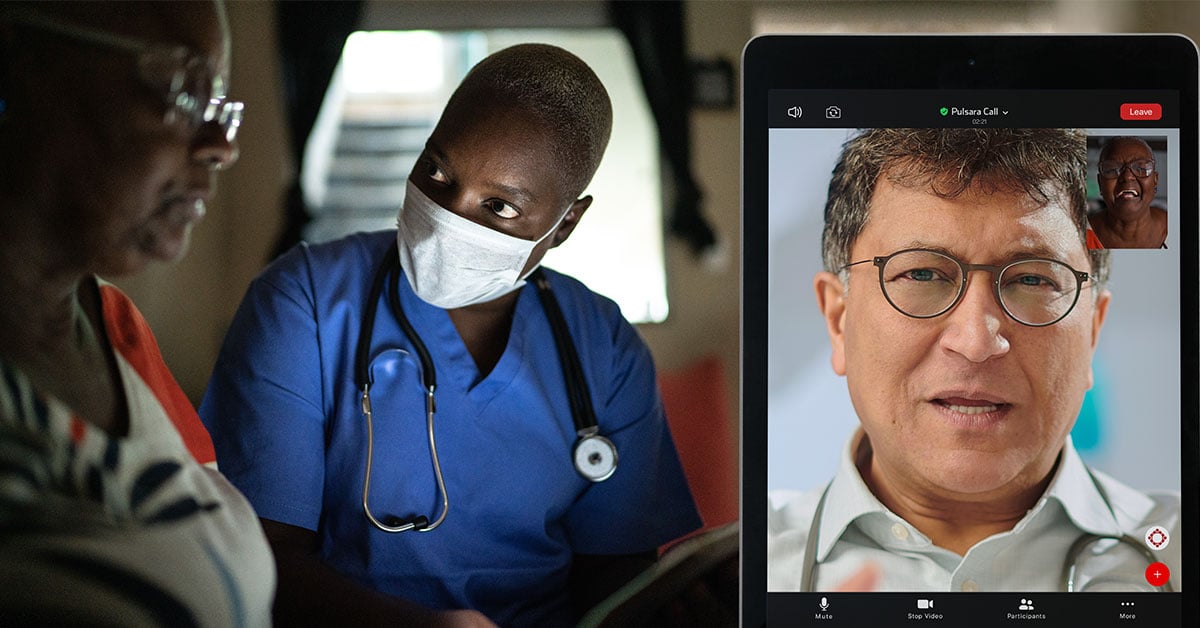

Recent research shows how Pulsara was successfully leveraged to connect more than 6,000 COVID-19 patients to monoclonal antibody infusion centers via...